Guest Post by Boni Hamilton

Guest Post by Boni Hamilton

One of my best memories of childhood happened at a family friend’s country farmhouse during an unexpected snowstorm that stranded us. Imagine seven kids, chattering and giggling, snuggled together in a single bedroom. Either of my parents could have squelched the noise with a look, but our friends’ parents – they were pushovers! That’s when the magic happened. Our friends’ mother sat down, picked up a book, and started to read aloud. The room was instantly silent and I remember thinking I can’t go to sleep because I don’t want to miss a word even as my eyes fluttered and closed.

That’s the only time I remember someone reading to me until fifth grade. Then classmate Jack read the Enid Blyton adventure books aloud after lunch each day. He kept us glued to our seats!

March is read-aloud month. A free downloadable infographic at readaloud.org (http://www2.readaloud.org/importance) lists the academic and social benefits for children when parents read aloud for 15 minutes a day every day. Although they recommend reading aloud until children are age 10, I read aloud to my then-disengaged-reader daughter through high school. She is now an avid reader.

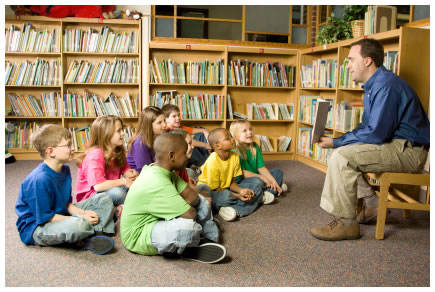

Teachers need to read aloud to children as well. As an educator who visits schools often, I have observed a disturbing decrease in the time devoted to reading aloud during the school day. In fact, I’ve learned that some principals prohibit their teachers from ever reading aloud to  elementary children! Parents, educators, and author allies should be confronting such principals.

elementary children! Parents, educators, and author allies should be confronting such principals.

When books are read aloud in school, teachers have two possible approaches: efferent or aesthetic. Efferent reading is when the teacher is using the text to teach a concept. For example, a fourth grade math teacher read Gator Pie by Louise Mathews (1995) to her students to get them to visualize dividing a pie into halves, thirds, fourths, eighths, and hundredths. The read aloud had an academic, or efferent, purpose. Efferent readings are valuable for helping children visualize academic concepts, build background knowledge, identify literary elements (theme, figurative language, etc.), and recognize genres (mystery, non-fiction, historical fiction, etc.) and text conventions (table of contents, captions, etc.). Mentor texts for writing are efferent reading – students are looking at stylistic choices for the academic purpose of mimicking them.

Aesthetic readings have the purp oses of igniting pleasure and imagination. The reader – a performer – shares the text and illustrations purely for enjoyment. This opens space for children to engage with the text from their own perspectives, to talk about their “wonderings” and “noticings.”

oses of igniting pleasure and imagination. The reader – a performer – shares the text and illustrations purely for enjoyment. This opens space for children to engage with the text from their own perspectives, to talk about their “wonderings” and “noticings.”

“What do you wonder? What do you notice?” These are the best questions a parent or teacher could ask while reading aloud a book. We adults are quick to draw attention to what we notice and wonder in a book, as though without our intervention children will miss something. But waiting for children to notice and wonder can give marvelous insights about their thinking. Here’s a transcript of one group of kindergarten children during an aesthetic reading of One Leaf Rides the Wind (2002) written by Celeste Mannis and illustrated by Susan Hartung. Students are looking at an illustration for the number six.

Brad: There’s six sandals. She’s holding part of them and part of them are on the ground.”

Lily: There’s more on the ground.

Levi: You can count them by 2’s.

Mark: There is two more kids inside.

Teacher: How do you know?

Mark: Because there are four shoes outside.

Teacher: How do you know they are kids’ shoes?

Mark: Because they are the same size as the girl’s.

Sarah: Why is she wearing socks with flip-flops?

Katie: I have a wondering. Why is she taking her shoes off in the garden?

Notice that although this is an aesthetic reading of the book, the children are making inferences and thinking about the illustration mathematically. The teacher’s questions are clarifying, not efferent.

A third grade teacher reads Letter from Rifka (1992) by Karen Hesse aloud each year during students’ study of immigration. On one level, this is an efferent reading, since the book provides students with insights about an immigrant girl’s experience in 1919. But the teacher chooses an aesthetic stance, and her students periodically stop the read-aloud to talk about what they “wonder” or “notice.” The students make the connections between what they are studying and the book, not the teacher.

When you are reading aloud, whether to one child or several, silence your own voice occasionally to elicit “wonderings” and “noticings” from your audience. What they say may surprise you!

Boni Hamilton thinks kids are great teachers — for one another and for adults. She has taught all ages (Pre-K – college); most disciplines, including special education, gifted programs, core content, technology, and art; in public and private schools for too many years to count. A perpetual learner, Boni is pursuing a second doctorate to learn how to help teachers work effectively in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms. Her second book, Integrating Technology in the Classroom: Tools to Meet the Needs of Every Student, will be released this spring.

I credit reading aloud for the reason my boys have such wicked vocabularies. They love to be read to, as all kids do, and I’m amazed at what parts of the stories enchant them. Reading aloud is the easiest thing to do and gives children lasting benefits.

This is very beneficial, Jean. Thanks for explaining the two types of readings we can do with children. Karen Hesse is one of my favourite writers.

I didn’t know these two terms until now, but they’re so useful. I’m especially drawn to books that can be used for both types of reading, but I like when they don’t have to be both all the time.

Very informative guest post. Boni sounds like a wonderful teacher!